Stephen Chilton (1975–2014) was one of my tutees. I taught him painting when he was studying for a BA (Hons) degree and afterwards an MA degree in Fine Art at the School of Art, Aberystwyth University. During that time we became good friends. Two years after completing his education, Stephen took his own life at the Little Orme, Llandudno. This suite of sound works is dedicated to his memory and to all men who are challenged by mental health issues or who have chosen to leave this life prematurely.

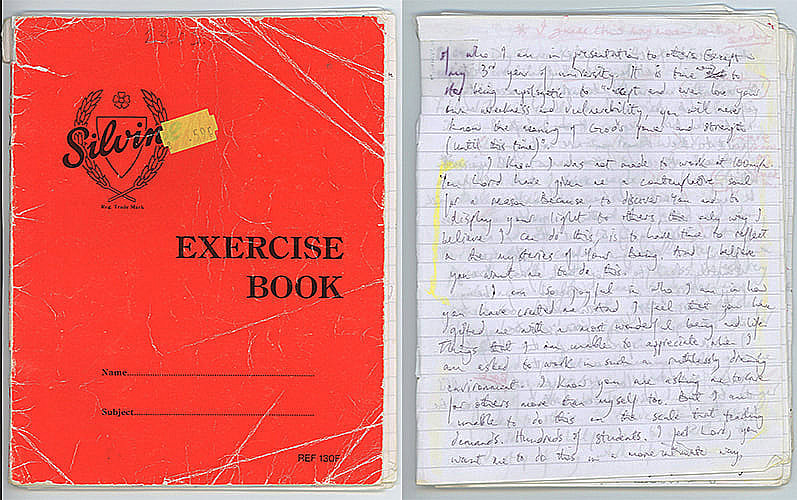

Stephen’s decision to pursue a postgraduate qualification in 2010 involved a great deal of soul searching. In his diary he candidly weighed up options, reckoned on the financial practicalities of giving up his position as a much loved secondary school art teacher, and endeavoured to discern God’s will for his life. Stephen was a Christian in the Roman Catholic tradition, and his account of this process includes seven prayers of petition for guidance and of thanksgiving for his gifts and calling.

Stephen’s decision to pursue a postgraduate qualification in 2010 involved a great deal of soul searching. In his diary he candidly weighed up options, reckoned on the financial practicalities of giving up his position as a much loved secondary school art teacher, and endeavoured to discern God’s will for his life. Stephen was a Christian in the Roman Catholic tradition, and his account of this process includes seven prayers of petition for guidance and of thanksgiving for his gifts and calling.

For him painting was a ‘visual representation of prayer’ ([diary], 20) – his prayers. The postgraduate degree would, he was persuaded, give him a longed-for opportunity to grow in devotion to his Lord and as an artist. For him these ideals were inseparable. Stephen’s written and painted entreaties to God have structured and informed my sonic realisation of the solemnity, exultation, lament, certainty, doubt, and surrender that characterised his painting and outlook during those last years.

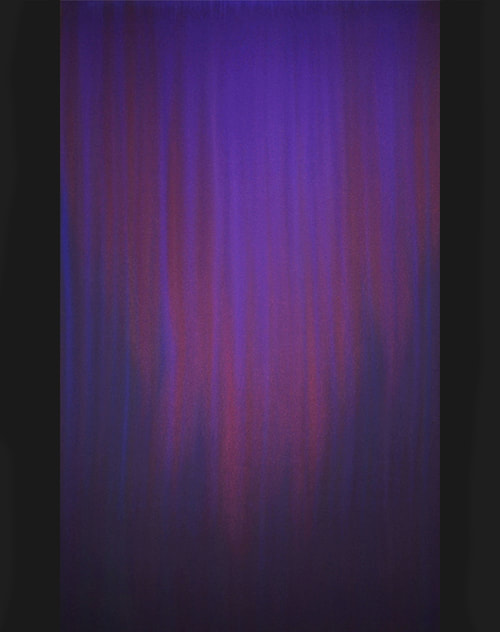

At the beginning of the second part of his MA, Stephen worked on a series of paintings entitled Musical Veils. They were an analogical response to music by Henryk Górecki (1933–2010). Arvo Pärt (b. 1935), Thomas Tallis (1505–85), and John Tavener (1944–2013), among others. He played their profoundly contemplative works in the studio to condition his heart, soul, and mind as he painted. The accompaniment, no more assertive than the ambient light under which he worked, saturated his aesthetic decisions and influenced the process of making directly and significantly:

Whilst painting, the music I listen to in the studio becomes embodied in the paintings. The sound enriches my visual choices in setting a colour response notation. The sequences of colour applied, then oscillate with the base-colour and I proceed to investigate the transitions of luminosity using translucent hues, each with a different pitch (Stephen Chilton – Fine Art).

The composer John Tavener described his compositions as ‘icons in sound’. Stephen’s aspiration was to embody sound in icons (Greek eikon = image). We both realised that it would be possible to convert his paintings into sonic equivalents. I had observed their construction sufficiently closely to conceive how the accrescence of colour layers might be recreated in terms of superimposed sounds. For example, the painting entitled Sanctus Light: Requiem (2013) is built up of thin, translucent washes of ultramarine, indanthrene blue, phthalocyanine blue, cobalt blue, purple, violet, and tints of white. These chromatic hues are all in the same quadrant of the colour circle. Musically, it is the equivalent of scoring a composition using only the range of notes (including quarter tones) between D♯ and F♯.

Stephen was planning to explore this relationship between colour and sound, between painting and music, in a PhD Fine Art degree. The collapse of his physical and mental well-being put pay to this. It is not my intention to fulfil his ambitions. I conjecture that he would have transformed images into sounds in a detached, measurable, and quasi-scientific manner. My approach, by contrast, represents a subjective, personal, and deeply felt response to his painting and, as significantly, to the painter, our discussions, and the abiding realisation of his absence.

The composer John Tavener described his compositions as ‘icons in sound’. Stephen’s aspiration was to embody sound in icons (Greek eikon = image). We both realised that it would be possible to convert his paintings into sonic equivalents. I had observed their construction sufficiently closely to conceive how the accrescence of colour layers might be recreated in terms of superimposed sounds. For example, the painting entitled Sanctus Light: Requiem (2013) is built up of thin, translucent washes of ultramarine, indanthrene blue, phthalocyanine blue, cobalt blue, purple, violet, and tints of white. These chromatic hues are all in the same quadrant of the colour circle. Musically, it is the equivalent of scoring a composition using only the range of notes (including quarter tones) between D♯ and F♯.

Stephen was planning to explore this relationship between colour and sound, between painting and music, in a PhD Fine Art degree. The collapse of his physical and mental well-being put pay to this. It is not my intention to fulfil his ambitions. I conjecture that he would have transformed images into sounds in a detached, measurable, and quasi-scientific manner. My approach, by contrast, represents a subjective, personal, and deeply felt response to his painting and, as significantly, to the painter, our discussions, and the abiding realisation of his absence.

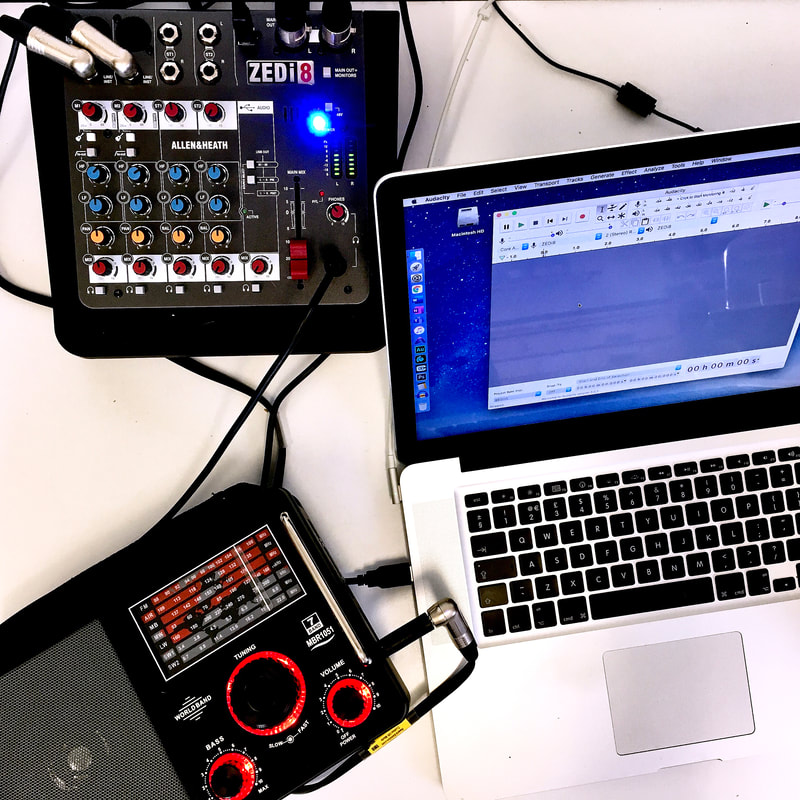

The suite has been, in part, informed by aspects of the natural world that had inspired Stephen’s work. In several of our tutorial discussions, we reflected on how like auroras (he was keen to see the northern lights one day) his veils of colour were. This atmospheric phenomenon is caused by electrically charged particles from the sun hitting the earth’s atmosphere. My sonification of this spectacle also involves the gaseous upper layers of the planet. I ‘painted’ using radio frequencies in the shortwave band. These are reflected or refracted from the ionosphere – a layer of electrically charged atoms in the atmosphere. I recorded only the static or white noise caused by weak radio and random electrical signals, natural electro-magnetic sounds occurring in the atmosphere, and noises of human origins produced by electrical equipment close to the radio’s antennae.

Like the white paint Stephen used to prime his canvases, this white noise underpins all seven prayers in one way or another. In two of them, the static and the signals buried within it constitute all of the sound material used for composition (‘Prayer 2’ and ‘Prayer 3’). Elsewhere, the white noise provides a preparatory course that underpins the subsequent layers of sound. On top of the primer Stephen put down what he referred to as a ‘base-colour’ – a strong saturated hue. In the context of the suite, the base colour is sometimes represented by a low-pitched drone (‘Prayer 4’). Musically, the note serves as the tonic or focus for all the other notes and noises that rise above it.

Stephen teased each painting into being by veiling translucent pigment. This was a necessarily slow and incremental process that permitted the base colour to remain partially visible through the upper layers, thereby creating a subtle depth. Likewise, several of my sound compositions evolve by the gradual superimposition of ‘translucent’ layers of sonic material over a base melody. The process is as follows: the melody is played through a digital reverberation device with a very long decay rate. The fading echoes of the notes accrue and are in turn echoed and overlaid, thereby generating dense and diffuse clouds of sound that slowly lose their definition and independence (‘Prayer 5’ and ‘Prayer 6’).

Stephen, I determined, would contribute to the compositional process. I read and recorded the texts of his seven prayers. They were then converted them from a high- to a low-resolution file format (WAV to MP3) and slowed down considerably. This fractured the sonic into a multiplicity of tiny parcels of digital information, some of which sound noisy or non-tonal in character, while others possess distinct tonalities and melodic qualities. Collectively, they provide an audible substance that, when excised, reversed, edited, collaged, looped, superimposed, and reordered, serves as the basis of musical composition.

Stephen, I determined, would contribute to the compositional process. I read and recorded the texts of his seven prayers. They were then converted them from a high- to a low-resolution file format (WAV to MP3) and slowed down considerably. This fractured the sonic into a multiplicity of tiny parcels of digital information, some of which sound noisy or non-tonal in character, while others possess distinct tonalities and melodic qualities. Collectively, they provide an audible substance that, when excised, reversed, edited, collaged, looped, superimposed, and reordered, serves as the basis of musical composition.

The suite begins and ends with surging white noise mimicking the waves of the sea (‘Prayer 1’ and ‘Prayer 7’). It was a sound that Stephen associated with Aberystwyth and was probably the last he heard in this life.

John Harvey

October 2021

Throughout the site, text in purple indicates a hyperlink.

John Harvey

October 2021

Throughout the site, text in purple indicates a hyperlink.